what ways did global music contribute to different cultures

Abstract

The digitization of music has changed how nosotros swallow, produce, and distribute music. In this paper, we explore the furnishings of digitization and streaming on the globalization of pop music. While some argue that digitization has led to more various cultural markets, others consider that the increasing accessibility to international music would issue in a globalized marketplace where a few artists garner all the attending. Nosotros tackle this argue by looking at how cross-state multifariousness in music charts has evolved over 4 years in 39 countries. Nosotros clarify two large-scale datasets from Spotify, the most pop streaming platform at the moment, and iTunes, one of the pioneers in digital music distribution. Our assay reveals an up tendency in music consumption diversity that started in 2017 and spans across platforms. There are now significantly more than songs, artists, and record labels populating the top charts than just a few years agone, making national charts more than diverse from a global perspective. Furthermore, this process started at the peaks of countries' charts, where diversity increased at a faster step than at their bases. We characterize these changes every bit a process of Cultural Divergence, in which countries are increasingly distinct in terms of the music populating their music charts.

Introduction

Digitization is arguably the biggest change the music market place has undergone over the concluding decades. In 2016, digital sales already accounted for more one-half of the revenues of the music industry (Coelho and Mendes, 2019). At that place are innumerable aspects on which digitization has impacted how we listen, produce, and commercialize music. For example, digital music is distributed at a nix marginal cost, meaning that digital audio tin can be reproduced advert infinitum without an actress cost on the side of the record characterization. For the consumer, streaming has had homologous effects. In streaming platforms, listening to new music does non behave an extra budgetary cost, every bit a listener only pays a flat monthly fee to subscribe to a platform like Spotify Footnote ane. This way, time and search costs are the but ones remaining in the fashion of music exploration. On the distribution side, online catalogs of music are orders of magnitude larger than those of physical stores due to the lack of infinite constraints, making a more than various offer of music (Anderson, 2006). At that place is bear witness that the increased availability of music has been accompanied by an enhanced multifariousness and quantity of music consumption (Datta et al., 2018). In this newspaper, nosotros explore the evolution of global diversity in the by years and find a clear trend towards global diversity in the music market.

Concerns of Cultural Convergence have been part of the public fence for decades. European governments, in particular, have made attempts to protect national cultural industries either directly (e.g. radio quotas) or indirectly (e.thousand. subsidizing national film product) (Ferreira and Waldfogel, 2010; Waldfogel, 2018). Because digitization granted easier admission to imported goods, predictions were that national cultural products were doomed, specially in smaller countries. Nonetheless, scientific research has not yet provided a definitive answer to whether this fear was well-grounded or not. There is evidence that digitization might have accelerated cultural convergence beyond countries in popular music (Gomez-Herrera et al., 2014; Verboord and Brandellero, 2018) while others notice an increasing interest in national artists (Achterberg et al., 2011; Ferreira and Waldfogel, 2010). Discrepancies almost likely stem from the inconsistency in the sample of countries included in these studies and the limited granularity of data available. Therefore, the question of whether digitization and streaming are currently propelling cultural convergence is open for debate. For similar cultural products, such as YouTube videos, global convergence is limited past cultural values (Park et al., 2017).

The contempo availability of datasets on music consumption beyond big numbers of countries has provided a way of overcoming some limitations of previous studies. In a recent example, Way and his collaborators, look at Spotify users' listening behavior and find that "home bias"—the preference towards national artists—is on the ascent globally (Way et al., 2020). A source of concern is the possible influence of a platform'due south endogenous processes on the behavior of its users. For instance, what appears as an enhanced preference for national artists could exist the result of changes in the recommendation algorithm. Alternatively, increased popularity of playlists like the New Music Friday, which are biased towards national artists (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018a) could produce a similar effect. Although far from common, major changes in the recommendation system of Spotify happen, the latest i beingness announced in March of 2019 (Spotify, 2019). As a event, recommendations are now more personalized, which, if the nationality of a user is taken into account, could generate increasing divergence betwixt countries by feeding users with national music. Co-ordinate to Spotify, up to one-5th of their streams can be attributed to algorithmic recommendations (Anderson et al., 2020), which may exist plenty to sway macro-level trends in music consumption.

We deal with platform-specific confounders by supplementing our analysis of Spotify information with a dataset from iTunes. It must be noted, however, that changes similarly affecting both platforms may exist, such equally the increasing use of recommendation systems or catalog expansions, besides as the mutual influence that would make these observations non-independent. Some other caveat of using platform-specific data is the fact that users of such platforms might not be representative of the unabridged population. Spotify users are disproportionately young and male when compared to their countries' population (Datta et al., 2018). Furthermore, the composition of users of a platform is in constant modify and the timing of adoption correlates with private listening habits. For instance, in Spotify, late adopters accept a stronger preference for local music than those who joined the platform early on (Way et al., 2020). To minimize the impact of these issues, nosotros reduce the sample of countries from the 59 bachelor to 39, keeping those in which Spotify is strongly established. Therefore, we expect the population of users in these countries to be more stable than in recently incorporated ones such as India, in which market penetration is quickly expanding. Additionally, this can exist considered as a inside-sample comparison (Salganik, 2019), which, given the large user base of Spotify, is of interest in and on itself.

In this newspaper, we tackle the question of whether digitized music consumption is globalizing or non past looking at the ecology of the national music charts of Spotify and iTunes in the past few years. In other words, by observing the global diversity in the charts we can discern whether popular music is converging or diverging across countries. More diversity across countries would be a sign of Cultural Divergence. On the other hand, a decrease in variety would be indicative of a procedure of Cultural Convergence across countries. We utilize the Rao-Stirling measure of diversity and its components (Stirling, 2007) to describe these trends. We find upward trends in the cross-national multifariousness of songs, artists, and labels, starting in 2017 in Spotify every bit well as in iTunes and ending in 2020 for Spotify. Popular music is thus diverging across countries in what we define equally Cultural Deviation. To complement previous studies, nosotros besides await at the diversity of artists and labels and find that these take increased in parallel. Ultimately, this paper describes trends in pop music across a large sample of countries, giving a more clear perspective of the cultural dynamics in the digital era.

Research groundwork

Winner-takes-all

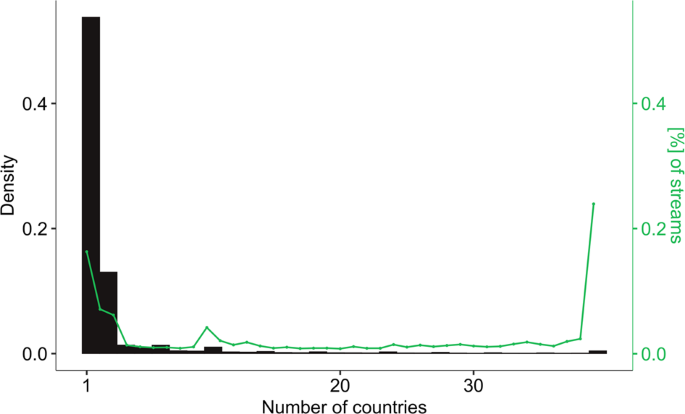

Cultural markets often exhibit a highly skewed distribution of success (e.g. Keuschnigg, 2015, Salganik et al., 2006). In the music market in item, a few hits expand across the globe while the bulk of popular songs merely hoard local success (see Fig. 1). Such inequalities are partly due to the scalability of cultural products, a property that refers to the fact that nigh of their cost is fixed – although this property does not apply to all cultural markets, existence the art field an exception – while marginal costs are relatively low. For instance, once a vocal is recorded or a book is written, the cost of making another copy is insignificant when compared to the initial toll of producing information technology, measured in time, inventiveness, or money, making these products scalable to large audiences. As a effect, demand is highly concentrated on the best alternatives, even when they are simply marginally better than the rest (Rosen, 1981).

Bars stand for the percentage of songs that got to the charts of exactly x countries. The green line represents the full number of streams that songs on each bin have accumulated while in the charts, as a measure out of popularity in the menses of analysis (2017-mid 2020).

Oftentimes this is an oversimplified view, since quality in cultural products is hard to define, and information technology is perceived (between others) every bit a function of previous success, thus creating path dependencies in the popularity of cultural products and artists. This process can be viewed as one in which information is accumulated, with consumers relying on it to moderate the quality uncertainty of their option of cultural products (Giles, 2007). Information is aggregated in the form of consumer reviews, sales rankings, or top charts. In a pathbreaking experimental written report, Salganik et al. (2006) found that information on other listener'due south musical preferences results in an amplified inequality of popularity when compared to a world of independent listeners. Using social cues in the grade of aggregated information might be beneficial for individuals in cultural markets in which preference is a thing of sense of taste, but in that location are multiple strategies to leverage such information and its fit varies betwixt individuals (Analytis et al., 2018). In the case of artists, during their careers, "pocket-sized differences in talent get magnified in larger earning differences" (Rosen, 1981). This "superstar effect"—defined every bit the previous success of an artist—is the near of import predictor of the popularity of a vocal, even when controlling for other factors (Interiano et al., 2018). Thus, the huge inequalities of success stemming from the scalability of cultural products and the social influence mechanisms intervening in their spread allows for the possibility of a few songs and artists to boss the charts across the globe.

In principle, both scalability, likewise as social influence processes, may accept gained bearing later on digitization and streaming. On the i mitt, digitization reduced the marginal costs of music production past eliminating the need to industry an album. Some transaction costs for digital music remain, such as copyrights and distributing platform fees, but overall, the barriers for music to menstruum beyond countries are substantially lower than in the pre-digital era. On the other manus, information is more abundant than ever earlier. Users tin can become near-real-time data on the listening decisions of millions of other users. On Spotify, anyone tin can search through the Tiptop 50 playlists tailored for every state. Each of them contains the nigh pop songs on the platform, which are updated daily. These playlists are extremely popular among users, for example, the Height 50 Global has over 15 meg followers. This drench of information is complemented with second-order feedback effects (Easley and Kleinberg, 2010) such as recommender systems, which might be luring listeners towards the most popular songs. For Spotify, there is evidence that users who rely more heavily on algorithmic recommendations listen to less diverse music and podcasts than those who discover music for themselves (Anderson et al., 2020, Holtz et al., 2020). In brusque, at that place are arguments to recall that the winner-takes-all effects characteristic of the music market might exist gaining begetting under the digital regime, decreasing the diverseness and increasing the concentration of the market in the hands of a few hit songs, superstar artists, and major labels.

The long tail

The idea of the long tail, first proposed past Anderson (2004) in a widely circulated press article sustains that online retailing has led to increased diversity in the consumption of music. This happened because online retailers do not accept the limitations of shelf infinite that traditional brick-and-mortar stores have, then their catalogs tin be most unlimited in size. The unlimited digital space can be filled with niche products that exercise not attract huge audiences only, scrap past chip, brand a divergence in terms of profits generated. In the book post-obit his commodity, Anderson (2006) goes beyond the original argument, suggesting that the Cyberspace has a conveying chapters for cultural products previously unattainable and its touch on on cultural markets has been broader than initially expected. Not but the distribution just likewise the production of cultural appurtenances has thrived as a result of the new technologies for distribution (eastward.g. online retailers), production (e.g. cheaper software), and consumption (e.g. flat fees). Some accept even qualified these changes as a renaissance of cultural markets (Waldfogel, 2018).

More than recently, Aguiar and Waldfogel have argued that the thought of the long tail fails to business relationship for the unpredictability of success in cultural markets (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018b; Waldfogel, 2017, 2020). When confronted with new artists, for instance, record labels accept a scant capacity to assess what will be the success of those artists. Nether such uncertainty, producers strive to pick those with better prospects but there will inevitably be miscalculations (due east.chiliad. the infamous Decca audition of The Beatles) and artists that were deemed unworthy of being promoted will end up reaping huge success, and the same in the reverse direction. In other words, earlier digitization, marketplace intermediaries held nigh of the conclusion ability over which products or artists were worthy of existence produced and which ones did not, the inevitable result of which was that some hits were lost. The reduced costs of production and promotion of digital cultural goods have made possible the product of these products. Different what the original idea of the long tail proposed, non all of them will be niche products and some will terminate up achieving unexpected popularity. The same goes for contained record labels, which now have better opportunities to promote their artists even with small budgets. There is evidence that indie artists and labels have gained relevance under the digital music regime (Coelho and Mendes, 2019). For instance, superlative-selling albums in the US produced by independent labels increased from 12% in 2000 to 35% in 2010 (Waldfogel, 2015).

Waldfogel and Aguiar refer to this phenomenon every bit the random long tail of music production. The random long tail contains those cultural goods that despite not existence attractive to traditional intermediaries can exist brought into production and, due to the inherent unpredictability of cultural markets, sometimes accomplish unexpected success. Accordingly, the more than unpredictable a cultural market is, the greater the number of unexpected hits. For case, the success of songs is more difficult to predict than that of movies, whose box-office earnings heavily depend on the budget and cast of the movie (Aguiar and Waldfogel, 2018b). In summary, these studies put forwards a vision of the music market in the digital era as more various and unpredictable.

Methods and data

Although in that location are multiple approaches to the study of diversity in social phenomena, Stirling'southward (2007) is i of the most influential and widely applied. More importantly, the Rao–Stirling diversity index has already been used to written report diversity in music taste, although at a different level of assay than here (Park et al., 2015; Fashion et al., 2019). The Rao–Stirling index consists of three components: diversity, balance, and disparity.

Variety is a function of the number of distinct units (songs, artists, or labels) in the charts on a given day. The more unique units the more variety there is in the charts. Naturally, in the example of songs variety is divisional by the fact that the same song cannot occupy more than 1 chart position per country so changes in multifariousness should exist interpreted, rather than the absolute size of the indicators (which also applies to the other measures of song diversity). We measure out diversity every bit the number of distinct units divided by the total number of chart positions. Remainder refers to how evenly distributed the system is across units. Here we measure balance as 1−Gini, a common measure of the inequality of a distribution. In this case, it is the distribution of chart positions across songs, artists, or labels. The more equally distributed positions are the higher the remainder in the arrangement. Chiefly, balance does not give any information about the number of units in the charts (variety). For case, label balance would be highest if two labels produce all the songs in the charts with equal shares likewise equally if every song in the charts was produced by a unlike label (and there were no songs in more than ane chart-state). The disparity is defined not by categories themselves but past the qualities of such categories or elements. In other words, the disparity is a mensurate of how different the elements of a system are. We ascertain the qualities of a song by its acoustic features Footnote 2 and then calculate the euclidean altitude between songs. In the case of artists, we define them by the cardinal trend of the acoustic features of their songs on the charts. The Rao–Stirling alphabetize combines variety, balance, and disparity into a single indicator of diversity Footnote iii.

Additionally, nosotros innovate Zeta multifariousness, a measure from biology. Zeta multifariousness was developed by Hui and McGeoch (2014) to tackle the issues with pairwise measures of diversity. Aggregated pairwise distance measures are consistently biased (Baselga, 2013) and, when the number of sites (countries) is large, they approximate their upper limit (Hui and McGeoch, 2014). More than importantly, Zeta variety gives a more nuanced view of the interplay between global and local hits. The distribution of the number of countries in which a song reaches the charts is right-skewed, as shown in Fig. ane, significant that most songs enter the charts of merely i or two countries. Every bit a consequence, what aggregated measures such as Rao–Stirling mainly capture is the effect of local hits. The influence of global hits is mostly null in such measures because of their paucity. Zeta diversity, on the other hand, measures distances at multiple orders. For instance, Zeta of social club three (ζ 3) represents the expected number of songs shared past groups of 3 countries. It is calculated by looking at all possible combinations of three countries and calculating the number of songs that each grouping shares. Higher orders or Zeta (e.m. songs shared by groups of 10 or more countries) capture the prevalence of more global hits. Here, we characterize Zeta by its key tendency, but other options are possible. As the order of Zeta increases its value decreases monotonically since there are always fewer songs charting in groups of three countries than in groups of two. In short, Zeta variety gives us a more than nuanced view of the distribution of success of songs across the charts compared to other diversity measures.

The data for the study comes from Spotify's top 200 charts and iTunes' top 100. We illustrate the analysis focusing on Spotify'south data because of the larger sample of countries (39 vs. 19). The entire list of countries can be found in Supplementary Table S1 online. Because iTunes data could not be retrieved from an official source (instead nosotros obtained information technology through Kworb.com), the results are reported only every bit a ways of externally validating our master findings. Spotify'south data covers the catamenia from 2017-01-01 to 2020-06-20, iTunes acme 100 daily charts for the flow 2013-08-14 to 2020-07-xvi.

Results

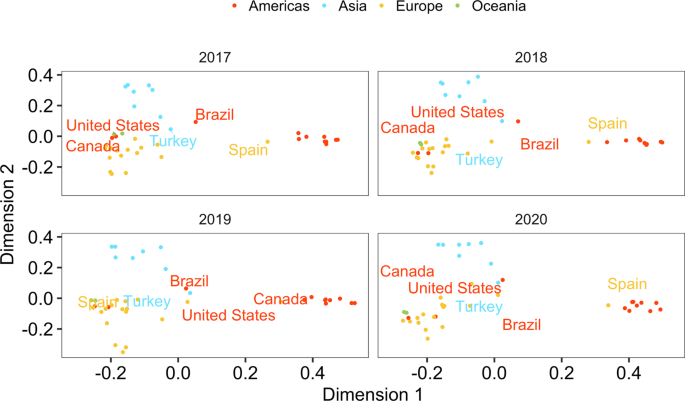

Figure two shows distances between countries as a function of the songs shared between their charts inside a year. Countries appear geographically clustered. One cluster is formed by Western countries of which Spain is the exception, being part of a different cluster, together with the Latin American countries. The third cluster encapsulates the Asian countries and Brazil. There are some noticeable anomalies, such every bit the closeness between Turkey and Brazil. Upon closer test, most of the songs shared between them are produced in the United states of america. This is likely the result of the small market penetration of Spotify, making for a user base of early on adopters more internationally oriented. Alternatively, it could be the result of a pocket-sized catalog of local music. In whatever case, the observable upshot is an over-representation of international (and mainly United states of america) hits in both countries' charts.

Jaccard distances calculated over annually constructed incidence matrices. Countries are colored according to the continent they belong to (ruddy: Americas, yellow: Europe, bluish: Asia, Green: Oceania).

Although positions are adequately stable over the years, if anything, clusters of countries seem to consolidate, being these iii groups more clearly discernible in 2020 than in 2017. Post-obit Park et al. (2017) we as well wait at the relationship between countries as a project of the two-mode network between countries and songs. The modularity of the network indicates the degree to which countries are amassed into modules beyond what would be expected on a random network. Modularity increased consistently from 2017 up to 2020 (run across Supplementary Fig. S4) indicating that countries within clusters are becoming more than similar in their music charts and, at the same time, drifting away from other clusters. These results are consistent with general notions of cultural, geographical, and linguistic distance which elsewhere have been proved to be the primary determinants of music taste similarities betwixt countries (Moore et al., 2014; Pichl et al., 2017; Schedl et al., 2017) although with a few exceptions such as the above-mentioned.

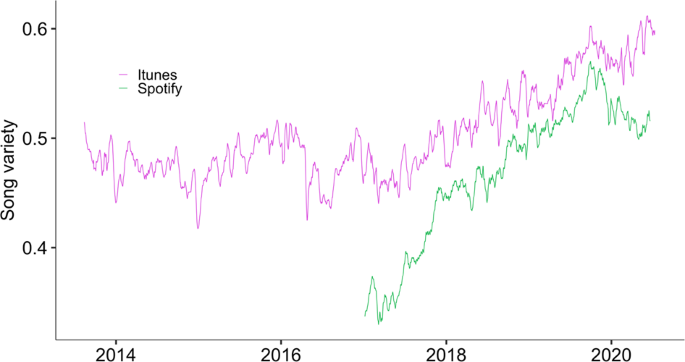

Seen equally a whole, the diversity of songs, artists, and labels has increased during this menstruum. Variety has grown non only on Spotify but on iTunes as well (Fig. 3). The resemblance betwixt the two trends is startling, specially if we consider how different these platforms are, one beingness a streaming platform with growing popularity (Spotify) while the other (iTunes) is a digital music shop whose user base of operations is in decay. The resemblance between the trends points to the external validity of the observations, although there could be some degree of influence between the platforms and thus they cannot be regarded equally completely independent observations. The upward tendency in variety starts in 2017 and plateaus at the end of 2019 on Spotify while information technology keeps increasing in iTunes.

Values range from 0 (same set of songs in every country) to 1 (no overlap betwixt the charts). Calculated for countries in both datasets (16 countries) and the same chart size (100 positions). Time series are calculated with daily frequency and smoothed over a 10-day window. Both Spotify and iTunes display consistent trends of increasing diverseness over fourth dimension.

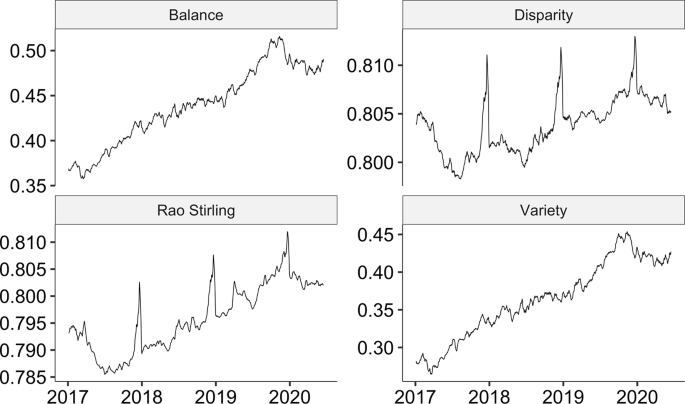

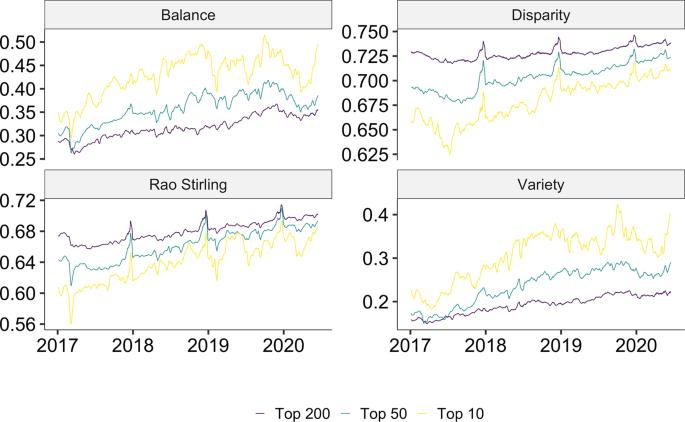

The increment in song diversity can exist observed in Fig. 4. Rest, disparity, and variety have all increased during the menstruation. The disparity indicator besides shows a strong seasonal burst effectually Christmas. This is consequent with other findings, suggesting that in countries in the Northern Hemisphere musical intensity declines around Christmas while the reverse is true for the Southern Hemisphere (Park et al., 2019). Overall diversity (Rao–Stirling index) rises from 2017 up to 2020 and then plateaus. Hence, not only at that place are more distinct songs in the charts (variety) merely these are acoustically more dissimilar (disparity) and their distribution over the chart slots is more than equal (balance) than at the beginning of the period.

Diversity, measured equally residuum, disparity, diverseness, or a combination of them, has been increasing consistently across countries with a plateau at the beginning of the year 2020. Besides the secular growth, disparity shows a strong seasonal component centered around Christmas.

As for songs, the diversity of artists has also grown. However, the trend is distinct at the head of the charts than at the lesser. By slicing charts at certain ranking positions we create a superlative 10, top 50, and summit 200 for each country. When it comes to residual and diverseness, the increment has been more pronounced at the head of the charts, which already presented a higher level at the showtime of the observed period. Nonetheless, disparity is lowest within the tiptop 10, indicating that the group of artists with songs on the head of the charts are stylistically more similar than those who just make it to the charts (a group that subsumes the former). What we tin derive from these trends is that, while at that place are proportionally more unique artists at the top of the charts, the music that those artists produce is relatively similar, as if there was an acoustic "recipe" for reaching the top of the charts. In general, artist diversity as a whole has increased at a similar step across strata of the charts (Fig. 5c).

All the components of artist diverseness accept increased steadily during the period. Every bit for songs, artist disparity bursts around Christmas. While balance and variety are higher at the peak of the charts, disparity shows the opposite pattern.

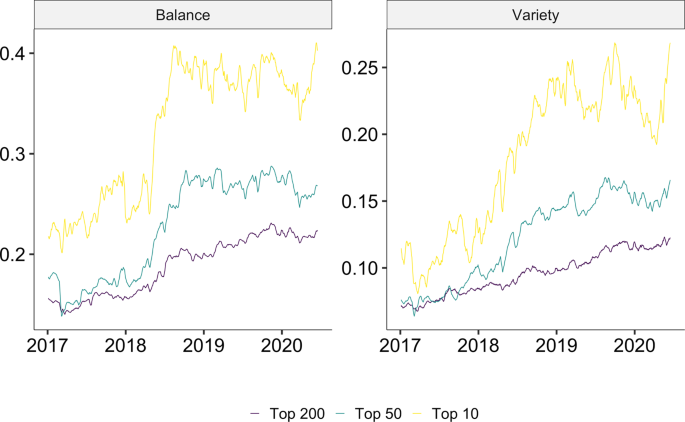

The increasing diversity of songs and artists in the charts has been accompanied past a more every bit distributed marketplace for record labels (Fig. 6a). Again, the trend is steeper if we look just at the caput of the charts. The number of distinct labels with at least one song in the charts has too increased in a stratified manner (Fig. 6b). In general, labels had on boilerplate fewer artists and songs on the charts at the end of the catamenia. While in the starting time half-dozen months of 2017 labels had on average 5.88 songs on the charts (and ii.19 artists), for the commencement half of 2020 it was one less song (and simply one.66 artists). Interestingly, the number of songs that each creative person got on the charts has increased slightly, going from 2.67 in 2017 to 2.96 in 2020 (comparing the kickoff half of each year).

The left panel shows the residual of labels over time for three sizes of the pinnacle nautical chart, displaying increases over fourth dimension peculiarly for the highest positions in the chart. The right panel shows the multifariousness of labels on the charts. The same patterns as for balance can exist observed.

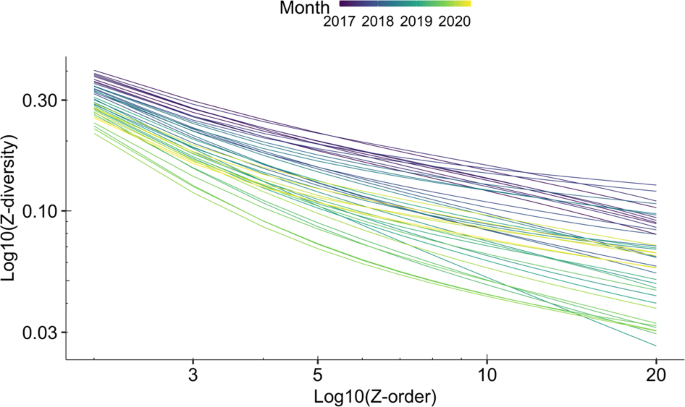

We can take a closer look at the interplay betwixt local and global hits through the Zeta diverseness measure out. Effigy vii presents the results for monthly Zeta diverseness measures of orders two—which is equivalent to pairwise distances—up to 20—the mean number of common songs shared by groups of 20 countries. Nosotros observe that across all orders of Zeta the mean multifariousness tends to subtract with time (brighter colors) which is consistent with the previous results Footnote 4. When we look at the disuse of Z-values along orders of Zeta (10-axis) we observe that it gets steeper over time. In other words, the slope of the regression with Z-values (y-axis) every bit a dependent variable and Z-lodge (x-centrality) as a predictor gets greater with time. Table 1 presents the results of a linear regression model that shows the increase in steepness over time. The substantive interpretation is that global hits have taken the lion's share of the increase in variety, condign an increasingly rare phenomenon.

The 10-axis represents the order of Zeta and the y-axis the z-value, or mean percentage of songs shared across groups of ten countries. Both axes are represented on a log10 calibration. The role of Zeta with order shifts down over time and becomes steeper.

Discussion

Past analyzing four years of data of music charts in 39 countries, nosotros find clear evidence of increased diversity in the music charts across countries. In the short period covered past this study, the number of unique songs, artists, and labels on the charts in our sample of countries has grown considerably. Despite the concerns expressed past several governments, particularly in Europe (Waldfogel, 2018, p. 220), popular music is not increasingly globalized. Instead, countries' pop music was among a process of Cultural Divergence that seemed to accept come up to a halt at the end of the observed period. The increase in diversity seems to be driven by a segmentation of the music market rather than an evenly heightened idiosyncrasy of music consumption. In other words, countries that were already close to 1 another in gustatory modality are becoming more than similar but increasingly different from other clusters of countries. Such clusters appear strongly determined, but not only, by geographical and cultural distance. Inquiry shows that regional clusters likewise differ in the audio-visual properties of the music that their populations listen to (Park et al., 2019). Therefore, although multifariousness is usually taken every bit a positive trait of a organisation, the sectionalisation which is driving the increase in diversity tin be a source of business.

We too show that multifariousness has been on the rise in terms of artists and record labels. Specially, the rising of label diversity rules out the possibility that the large labels are producing pop music fitted to different markets, as the proponents of glocalization would argue. As a event of these trends, not only songs might exist increasingly distinct beyond countries, but also their production and distribution.

Whether information technology is the preferences of users or shifts in the production and distribution of music that are driving these changes is not clear. The possibility that Cultural Divergence is the result of a random long tail in music production is more consistent with the pace and ubiquity of these changes than preference-based accounts of the aforementioned phenomenon. Therefore, as an alternative to preference-based explanations of the increase in habitation bias (Style et al., 2020) and global multifariousness, we propose that these observations could be explained past changes in music production. 1 first source of business organization with the preference-based explanation stems from the speed and ubiquity of the observed changes. Cultural shifts of this scale are generally slow, comparable in speed to the development of traits in fauna populations (Lambert et al., 2020). Also, there is evidence that changes in the aggregated preferences of a population are mostly driven by generational replacement (Vaisey and Lizardo, 2016). Instead, we debate that field configurations tin more rapidly sway macro-patterns by conditioning the opportunities of individuals. In the instance of music, the random long tail of music production may have increased the bachelor options of users to limited their idiosyncratic preferences, which, being to some extent geographically adamant (Ferreira and Waldfogel, 2010; Gomez-Herrera et al., 2014; Way et al., 2020), would likely effect in national music charts drifting abroad from each other.

Methodologically, this research shows the potential of Zeta diversity, a measure out devised for the study of biodiversity, to gauge the globalization of cultural products at dissimilar levels. Since truly global hits are extremely rare phenomena when compared to songs that reach in minor groups of culturally like countries, they conduct very low weight when calculating pairwise distances, which is a mutual way of looking at cross-national diversity. National charts could drift apart without affecting the likelihood of the eventual striking to spread globally and conventional pairwise measures would non pick this dynamic. As we bear witness, this has not been the instance for the music market, in which the positive trend in diversity has been accompanied past a significant decrease in the spread of global hits. The awarding of Zeta diversity is not without issues, 1 of them being that its adding is computationally demanding when compared with the other measures of multifariousness presented here, considering of its combinatorial nature. In render, it offers relatively stable estimates of rare events, a useful feature when studying heavy-tailed distributions in general, and cultural markets in detail, in which global hits are highly unlikely simply more than consequential in terms of collective attention than the more mutual local hits. More broadly, our analysis applies mathematical methods from ecology to analyze the consumption of cultural content. This interface between disciplines has other applications, for example, to understand the dynamical reorganization of user activity on social media (Palazzi et al., 2020). Furthermore, our piece of work builds on existing literature utilizing methods from ecology to study musical taste and consumption (Park et al., 2015; Way et al., 2019).

To conclude, our results run counter to the notion of an unbounded market that can exist distilled from the idea of globalization. Information technology also challenges the expectations of the winner-takes-all set up of theories that predict heightened inequality in the distribution of success under decreased restrictions to global expansion. Instead, the music market has become, in this short menstruation, more hostile to the spread of hits across the globe. From a positive perspective, this ways that "national cultures" are not disappearing, although this might come at the expense of a more segmented market place in bundles of culturally similar countries, and the risks associated with such segmentation if spread, for example, from esthetic to normative judgments.

Information availability

Information and code for the analyses are available at https://github.com/PabloBelloDelpon/Spotify_paper.

Notes

-

Users also have the option to get free access to a limited version of the platform, which is ad-supported.

-

Spotify measures the acoustic features of each song and groups them into the followingcategories, all of which we include in the assay: danceability, energy, key, loudness, mode,speechiness, acousticness, instrumentalness, liveness, valence, tempo, and duration.

-

More than precisely, Rao–Stirling is calculated as in Stirling (2007): D = ∑ it(i≠j) d ij ⋅p i ⋅p j , where p i and p j are the proportions of elements i and j in the organisation and did is the euclidean altitude betwixt their corresponding acoustic representations.

-

Zeta multifariousness is measured in the contrary direction than the previous indicators of diverseness. Higher values bespeak more than overlap of songs across charts and smaller values signal less overlap.

References

-

Achterberg P, Heilbron J, Houtman D, Aupers S (2011) A cultural globalization of popular music? American, Dutch, French, and German language popular music charts (1965 to 2006). Am Behav Sci 55(v):589–608

-

Aguiar Fifty, Waldfogel J (2018a) Platforms, promotion, and production discovery: Evidence from spotify playlists. JRC digital economic system working paper, 2018/04

-

Aguiar L, Waldfogel J (2018b) Quality predictability and the welfare benefits from new products: evidence from the digitization of recorded music. J Polit Econ. https://doi.org/10.1086/696229

-

Analytis PP, Barkoczi D, Herzog SM (2018) Social learning strategies for matters of sense of taste. Nat Hum Behav 2(6):415–424

-

Anderson A, Maystre 50, Anderson I, Mehrotra R, Lalmas M (2020) Algorithmic effects on the multifariousness of consumption on spotify. In: Proceedings of the web briefing 2020, Taipei, Taiwan. ACM, pp. 2155–2165

-

Anderson C (2004) The long tail. Wired. https://world wide web.wired.com/2004/10/tail. Accessed 20 Jul 2021

-

Anderson C (2006) The long tail: why the futurity of business concern is selling less of more. Hachette

-

Baselga A (2013) Multiple site dissimilarity quantifies compositional heterogeneity among several sites, while average pairwise dissimilarity may be misleading. Ecography 36(ii):124–128

-

Coelho MP, Mendes JZ (2019) Digital music and the decease of the long tail. J Passenger vehicle Res 101:454–460

-

Datta H, Knox Grand, Bronnenberg BJ (2018) Changing their tune: how consumers' adoption of online streaming affects music consumption and discovery. Market Sci 37(1):v–21

-

Easley D, Kleinberg J (2010) Networks, crowds, and markets: reasoning almost a highly connected world. Cambridge University Printing

-

Ferreira F, Waldfogel J (2010) Pop internationalism: has a half century of globe music trade displaced local culture? Technical Written report w15964. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

-

Giles DE (2007) Increasing returns to information in the Us popular music manufacture. Appl Econ Lett 14(v):327–331

-

Gomez-Herrera Eastward, Martens B, Waldfogel J (2014) What's going on? Digitization and global music merchandise patterns since 2006. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2535803. Social Scientific discipline Research Network, Rochester

-

Holtz D, Carterette B, Chandar P, Nazari Z, Cramer H, Aral S (2020) The engagement-diverseness connexion: prove from a field experiment on spotify. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3555927, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY

-

Hui C, McGeoch MA (2014) Zeta diverseness every bit a concept and metric that unifies incidence-based biodiversity patterns. Am Nat 184(v):684–694

-

Interiano M, Kazemi K, Wang L, Yang J, Yu Z, Komarova NL (2018) Musical trends and predictability of success in contemporary songs in and out of the pinnacle charts. R Soc Open Sci five(v):171274

-

Keuschnigg M (2015) Product success in cultural markets: the mediating role of familiarity, peers, and experts. Poetics 51:17–36

-

Lambert B, Kontonatsios Thou, Mauch M, Kokkoris T, Jockers M, Ananiadou S, Leroi AM (2020) The step of modern culture. Nat Hum Behav 4(4):352–360

-

Moore JL, Joachims T, Turnbull D (2014) Taste space versus the world: an embedding assay of listening habits and geography. In: Proceedings of the 15th International Society for Music information retrieval briefing, Taipei, Taiwan

-

Palazzi MJ, Solé-Ribalta A, Calleja-Solanas V, Meloni S, Plata CA, Suweis S, Borge-Holthoefer J (2020) Resilience and elasticity of co-evolving information ecosystems. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.07005

-

Park Yard, Park J, Baek YM, Macy M (2017) Cultural values and cantankerous-cultural video consumption on YouTube. PLoS ONE 12(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177865

-

Park Thou, Thom J, Mennicken S, Cramer H, Macy M (2019) Global music streaming data reveal diurnal and seasonal patterns of affective preference. Nat Hum Behav 3(iii):230–236

-

Park M, Weber I, Naaman M, Vieweg South (2015) Understanding musical diversity via online social media. In: Proceedings of the ninth international AAAI conference on web and social media, Oxford, UK

-

Pichl M, Zangerle E, Specht G, Schedl M (2017) Mining culture-specific music listening behavior from social media data. In: 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM), Taichung. IEEE, pp. 208–215

-

Rosen Due south (1981) The economics of superstars. Am Econ Rev 71:845–858

-

Salganik MJ (2019) Bit past chip: social research in the digital age. Princeton University Press, Princeton

-

Salganik MJ, Dodds PS, Watts DJ (2006) Experimental written report of inequality and unpredictability in an bogus cultural market Science 311(5762):854–856 https://doi.org/10.1126/scientific discipline.1121066 American Clan for the Advancement of Science Section: Report

-

Schedl M, Lemmerich F, Ferwerda B, Skowron 1000, Knees P (2017) Indicators of state similarity in terms of music taste, cultural, and socio-economic factors. In: 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM), Taichung. IEEE, pp. 308–311

-

Spotify (2019) Our playlist ecosystem is evolving: hither's what it ways for artists & their teams—news—spotify for artists. https://artists.spotify.com/blog/our-playlist-ecosystem-is-evolving. Accessed 10 Nov 2020

-

Stirling A (2007) A general framework for analysing diversity in scientific discipline, applied science and lodge. J R Soc Interface 4(15):707–719

-

Vaisey S, Lizardo O (2016) Cultural fragmentation or acquired dispositions? a new approach to accounting for patterns of cultural change. Socius ii:1–fifteen

-

Verboord M, Brandellero A (2018) The globalization of popular music, 1960–2010: a multilevel assay of music flows. Commun Res 45(4):603–627

-

Waldfogel J (2015) Digitization and the quality of new media products: the instance of music. In Economical analysis of the digital economy. The Academy of Chicago Printing, pp. 407–442

-

Waldfogel J (2017) The random long tail and the golden age of boob tube. Innov Policy Econ 17:1–25

-

Waldfogel J (2018) Digital renaissance: what information and economics tell united states of america about the future of popular culture. Princeton University Press, Princeton

-

Waldfogel J (2020) Digitization and its consequences for creative-industry product and labor markets. In: The role of innovation and entrepreneurship in economic growth. The University of Chicago Press, p. 42

-

Way SF, Garcia-Gathright J, Cramer H (2020) Local trends in global music streaming. In: Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol. 14. pp. 705–714

-

Fashion SF, Gil Southward, Anderson I, Clauset A (2019) Ecology changes and the dynamics of musical identity. In: Proceedings of the 13th international AAAI conference on web and social media, vol. 13. pp. 527–536

Acknowledgements

D.G. acknowledges funding from the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF) through project VRG16-005. We thank Marc Keuschnigg and Paul Schuler for their insightful comments on previous versions of this commodity.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linköping Academy.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher's note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, equally long as yous give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and point if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this commodity are included in the article's Artistic Eatables license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the fabric. If material is non included in the commodity'southward Artistic Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted employ, yous volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bello, P., Garcia, D. Cultural Divergence in popular music: the increasing diversity of music consumption on Spotify across countries. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 182 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00855-one

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1057/s41599-021-00855-1

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-021-00855-1